Objests for Objoys: the attraction of the unforeseen, Stephen Wright

Semaine

“The moment the object jubilates gush forth its qualities” —Francis Ponge

Objests

The various works of Michel de Broin complement one another like the components of a constantly expanding visual vocabulary. As if the existent vocabulary were never sufficient to express the here-and-now; as if life somehow eluded it. In this visual language game, governed by unpredictable rules that can be codified only retrospectively, like those governing the grammar of dreams, the different pieces resemble one another like words in a language. The often playful objects that Michel de Broin injects into the real evoke marvellously what poet Francis Ponge referred to as “objests”: playful, jesting objects, glorifying the referent on the one hand while upstaging it on the other. In De Broin’s work, in other words, art’s poetics lie in the breach between words and things, in the play between the object and its frame. Piece after piece, Michel de Broin’s vocabulary asserts itself and softens up at the same time, for though the objects he stages are universally recognisable, and immediately intelligible, they invariably turn out to be more mysterious upon reflection – in much the same way as Ponge’s neologism.

Objoys

Language is needed to create language, words to convoke more words, objects to engender still others. Yet if De Broin’s visual vocabulary is to that degree sui generis, it also draws upon its environment. The artist combines materials laden with an irrepressible yet disquieting social, emotional and erotic charge; a charge that can be bracketed off but never evacuated; a charge that links elements together until the new object becomes “jubilant” and communicative. The fleeting and vacillating moment of jubilation that the artist experiences when he manages both to express the object and himself might be referred to – once again following Francis Ponge (clustering lexical fragments together the way De Broin does with objects from his everyday) – as one of utter “objoy”.

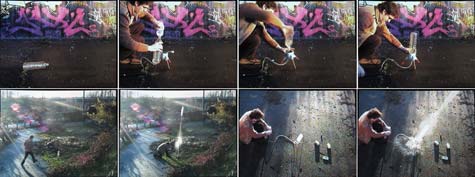

Michel de Broin thus juxtaposes incongruous elements, or inserts them into unexpected contexts. The art of juxtaposition is also a game, a joy, where the frivolous yields to the serious, and vice versa, in the spontaneity of adaptation to circumstances. Art, like conversation, if it is to escape from tedium, feeds constantly on the new; we have become accustomed to expecting the unheard-of. But the unforeseen – that which one will neither capture nor master, but in the face of which one has the sensation of truly experiencing something – is what is most rewarding but also most puzzling about art as experience. Each objest, each objoy, in short each work is the unforeseen affirmation of its own occasion. This raises the question of where art is specifically to be found. For though Michel de Broin certainly produces artworks, is the artwork embodied in the gadgets and devices he produces, in objects whose coefficient of artistic visibility is so low as to almost certainly trigger discussions with customs officers and police inspectors as to their true ontological status? Or do Michel de Broin’s works manifest themselves rather in the videos which show the deployment of his ambivalent objects in public spaces? What exactly is the status of these strange objects, which appear as at once anxious, jubilant and ejaculatory?

Anxious objests

It was the American art critic Harold Rosenberg who coined the term “anxious objects” to designate those objects that today fill our galleries, museums and public spaces, whose status appears so decidedly unstable that they seem to be waiting for some gesture or decision on our part to cease existing as mere objects and to change status, to shift from one ontological landscape to another, in order to become artworks. Yet why, and under what conditions, does some object or other become “anxious”? It is not anxious in its capacity as an object, but becomes so only once its objecthood has been potentially embellished by a further status as art. An artwork is anxious when its coefficient of specifically artistic visibility is reduced, either by the absence of artistic intentionality or by the absence of an artistic framework. An object is anxious when there is play between it and its frame. And Michel de Broin’s objects are all the more anxious in that they are intrinsically unstable, of a playful but nevertheless disquieting strangeness.

Ejaculatory objoys

I recall on one occasion talking about the video Reparations (voluntary participation in a waste re-enhancement program) to a friend, adding that Michel de Broin was obviously an ejaculatory artist. She asked if we – that is, the artist and I – had ever ejaculated together. I gave the question some serious thought, anxious to avoid a premature comeback to such a fundamental (and slightly unexpected) question, before answering that ejaculation being what is most difficult to achieve, we had not yet managed it, in spite of our efforts – and that that was why we had art. In the words of Russian Formalist V. Chklovski:

“To render the sensation of life, to feel objects, to experience that stone is stone, there exists what is called art. Art’s goal is to give a sensation to the object as vision and not as recognition; art’s device is the device of singularising objects and the device that involves obscuring the form, increasing the difficulty and duration of perception. The act of perception in art is an end in itself and must be prolonged; art is a means of experiencing the becoming of the object, what has already ‘become’ is of no consequence for art.” 1

Michel de Broin explicitly acknowledges his elective affinity for Russian Formalism; and it seems to me that it is explained above all by his concern with perception, which also constitutes the back bone of Chklovski’s aesthetic theory. According to Chklovski, artistic language is a sort of ostentatious visual dialect whose vocation it is to trigger the awakening of renewed perception. The object’s artistic use can be observed and measured by the strangeness of its form – “difficult, obscure, rife with obstacles” he asserts 2 – which is perceived as unusual by comparison with an ordinary object: form is thus the distinctive feature aesthetic perception. At the core of Chklovski’s system, one encounters the opposition between perception in the most emphatic sense and acquired habit – an opposition that is determinant in Michel de Broin’s work as well. Habit is the depleted form of perception that has become mechanical, almost algebraic. The stultifying of perception leads to myopia with regard to the object; instead of “seeing” it, one merely “recognises” it, perceiving it in a habitual way. The function of art, by contrast, is to revitalise perception of the object, to wrest it from habit in order to bring conscious experience back to life. The artwork must unleash a sudden awareness of the surfaces and shapes of the object and the world that has been recharged with all its freshness and existential horror. The work only rises to the status of aesthetic experience once it manages to provoke a renewal of perception in the viewer; the work succeeds if and when it “creates a particular perception of the object, creating its vision rather than its recognition.”3 Art is a device that is “consciously created to free perception from automatism; its vision represents the goal of the creator and it is constructed artificially, in such a way that it arrests perception upon itself…”4 De Broin lashes out playfully at the force of habit, his art deploying all its force to abrogate the deadening pact of mediocrity that the real is forever sealing with the possible.

1. Chklovski, “Art as Device”, cited from the French edition translated by T. Todorov, in Théorie de la littérature (Paris: Seuil, 1965), p.83. Chklovski was the forefront theorist of Russian formalism and the group Opoïaz (Society for the investigation of poetic language). Two aspects of his aesthetic system are of relevance with regard to the work of Michel de Broin: his theory of estrangement (ostranenie), and his conviction that the art’s role is constantly to renew perception by disclosing its own devices (obnazhenie priema).

2. Ibid., p. 95.

3. Ibid., p. 90.

4. Ibid., pp. 94-95.